Changing times – a hoard of small change from Castle Street

57 Castle Street

23rd June 2025

A Causeway Safari Park Tale

4th September 2025Changing times – a hoard of small change from Castle Street

A coin hoard from Castle Street

In July 2025, Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council purchased a property at no.57 Castle Street, Ballycastle, with the intention of extending Ballycastle Museum sideways to the west from the existing location in no.59 . The purchase was part of the council’s commitment to a wider programme of restoration and refurbishment of the museum supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund. During the clear-out process, various objects were salvaged to help tell the history of the building. Among those was a small cardboard box at the back of a cupboard with a curious surprise.

- Coins of Victoria

- Coins of Edward VII

- Coins of George V

- Coins of George VI

- Coins of Elizabeth II

- Irish and Manx coins

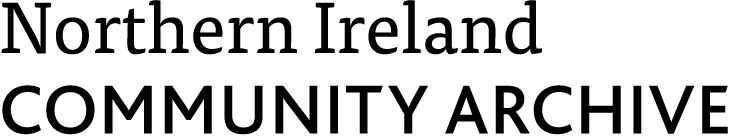

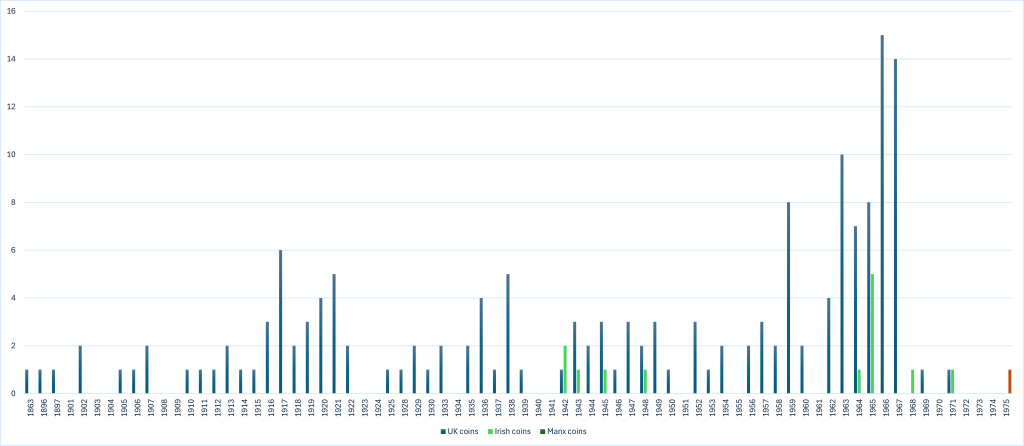

The box contained 177 coins dating from 1863-1975. All but one coin (a cupro-nickel 1969 five pence) were copper-alloy small change. Among the coins, 162 were currency of the United Kingdom (halfpennies, pennies, and threepence), 14 coins were from the Republic of Ireland (halfpennies and pennies), and one from the Isle of Man (halfpenny).

The individual coins are mostly unremarkable – many are worn or show other signs of damage from use. However, taken as a hoard – in archaeological terms, a hoard is any find of two or more coins from a single location – the coins start to tell their own story.

The first thing to note is that almost all of the coins date back to the period before decimalisation, when UK coinage was divided into pounds (£), shillings (s), and pence (d) – often shown as £.s.d. There were 12d to 1s, and 20s to 1£. Each pound was therefore worth 240 pence, a legacy of Roman coinage where a pound of silver would produce 240 denarii.

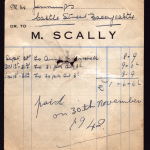

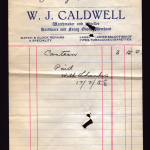

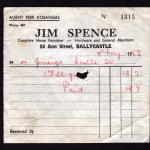

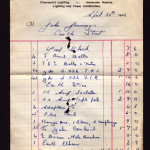

You can see plenty of examples of prices set out as £.s.d among the many receipts in the museum collection. A small sample are shown below, and a link to find out more.

On 15th February, 1971, the UK switched to a decimal currency system, replacing the old £.s.d. with a system where each pound was worth 100 pence. The last pre-decimal coins intended for circulation were produced in 1969. In the same year, new decimal five pence coins were introduced to replace the old shillings.

New decimal pennies were issued in 1971 to replace the older issues. Until 1981, the new decimal coins were struck as ‘new pence’ to distinguish them from the older pennies.

Pre-decimal pennies and threepence pieces continued to be legal tender until 31st August, 1971, although some coins remained in use for many years. People could pay in ‘old’ money, and receive their change in new pence.

The pre-decimal shilling (12 old pence) was worth 5 new pence in the decimal system and continued to be legal tender until 1990. Two-shilling coins continued to be accepted until 1992.

|

A note of terminology The wide range of pre-decimal denominations led to a wide range of informal names. A penny could be a ‘wing’, while the threepence could be known as a thruppence, thruppenny, or ‘three d’. A sixpence might be known as a ‘tanner’, a ‘bob’ for a shilling or ‘two bob’ for a florin’. A half crown was also known as a half dollar. Just as today, a pound might be known as a quid. |

- Halfpenny, 1963

- One penny, 1967

- Threepence, 1967

- 5 New Pence (=12 old pence), 1969

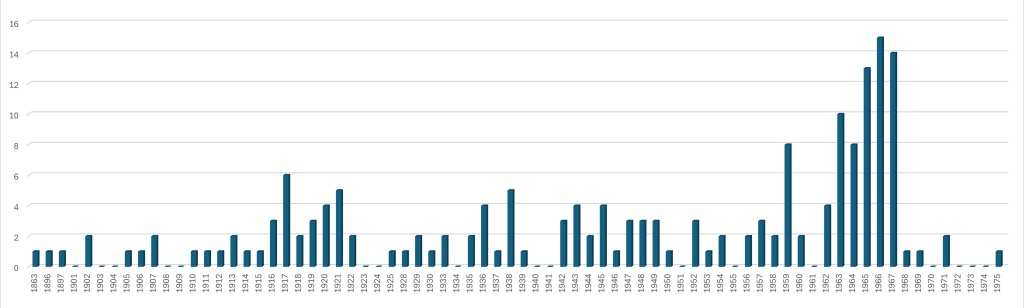

Looking at the spread of coinage in the hoard, we can see a relatively even distribution of low numbers of coins from 1863-1958 when numbers start to rise, peaking in 1965-1967 (42 examples), before dropping away sharply. There is one further pre-decimal coin (1968), and then four decimal outliers, a 1969 five pence coin, two halfpennies in 1971 and the Isle of Man half penny from 1975.

The surfaces of all the coins show some evidence of use – scratches and worn, flattened surfaces. These signs of wear are to be expected on coins that have been circulated, passing from hand to hand and being knocked against each other in pockets, purses and tills. The earlier coins tend to be the most worn, demonstrating that they were in circulation for the longest period, and showing that coins over 100 years old were still in use at or just before the date of deposition.

- Victoria penny, 1863 (reverse)

- Edward VII penny, 1907 (reverse)

- George V penny, 1917 (reverse)

- George VI penny, 1947 (reverse)

- Elizabeth penny, 1963 (reverse)

Changing times, changing faces

Including coins over a period of 112 year, the Castle Street hoard illustrates the changing portraits of the British monarchs during that period. It had become customary for each monarch to face in the opposite direction to their predecessor on their coin portraits since the seventeenth century and that tradition was generally followed as shown on the coins in the hoard.

- Victoria penny, 1863 (obverse)

- Victoria penny, 1897 (obverse)

- Edward VII penny, 1910 (obverse)

- George V penny, 1919 (obverse)

- George VI halfpenny, 1950 (obverse)

- Elizabeth II halfpenny, 1962 (obverse)

- Elizabeth II new penny, 1971 (obverse)

There are two different portraits of Queen Victoria, the so-called ‘Bun Head’, portrait in use from 1860-1889 showing the queen wearing a wreath with her hair in a bun (although our example is very worn), and the later ‘Old Head’, produced 1893-1901, depicting the queen wearing a tiara and veil.

Edward VII, George V and George VI are each represented by only a single portrait type.

Elizabeth II is represented by two portraits. Most of the coins bear the youthful head wearing a laurel wreath produced from 1953-1968. A second portrait was produced in 1968-1985 to coincide with decimalisation showing a slightly older queen wearing a tiara.

Coins from the Republic of Ireland

Coinage for the Irish Free State was introduced in 1928 to replace the British coins that had continued to be used in Ireland since Partition in 1921. The first series were marked Saorstát Éireann, but this was changed to Éire in 1939 with the establishment of the Republic of Ireland. Like the UK, Ireland decimalised its currency in 1971.

Until 1979, Irish coinage was produced by the Royal Mint in London to the same dimensions as British coins, and guaranteed by the Bank of England. While they were not technically accepted as legal tender in the UK, Irish coins continued to circulate in Northern Ireland, being more common in larger towns, cities and in border areas. Despite being some distance from the border, 14 coins from the Republic of Ireland occur in the Castle Street hoard as a testimony of this circulation.

- Irish halfpenny, 1942 (obverse)

- Irish halfpenny, 1942 (reverse)

- Irish penny, 1964 (obverse)

- Irish penny, 1964 (reverse)

- Irish new penny, 1971 (obverse)

- Irish new penny, 1971 (reverse)

Curiously, the Irish coins fall into two clusters: one group of five coins from 1942-1948, and another group of nine from 1964-1971. These clusters may be purely circumstantial, but they do coincide with specific economic and social events that might explain the increased presence of Irish coinage circulating in the northeast corner of Northern Ireland.

Irish copper-alloy small change tended to be minted in relatively small numbers (for example, just 312,000 pennies in 1940, and 4.7 million pennies in 1941). However, there were a number of years with notably increased production.

In 1942, 17.5 million Irish pennies were struck at the Royal Mint. This steep increase counterbalanced production of British coins at the mint where the striking of copper coins largely ceased due to the impact of the Second World War and the need to use copper for the manufacture of armaments and munitions. With a shortage of UK small change, there would be little wonder if there was an increase in the circulation of Irish coins of the same denominations across Northern Ireland.

Following 1943, Irish coin production returned to its usual levels with 4.8 million pennies produced in 1948, 2.4 million in 1950 and only 1.2 million in 1962. There was another peak in production from 1963 with 9.6 million pennies produced, rising to 11.2 million by 1965, and 30 million in 1968 ahead of the change to decimalisation. This second surge of Irish coinage in the 1960s is also mirrored by the presence of Irish coins in the hoard dating to this period.

Graffiti on a coin of George V

One penny, dating to 1915 during the reign of George V is another curiosity, bearing a graffito on both the coin’s obverse (heads) and reverse (tails). On both sides of the coin, somebody has roughly incised what looks to be W rotated 90 degrees on its side to resemble a Greek sigma (Σ).

- George V penny with graffito, 1915 (obverse)

- George V penny with graffito, 1915 (reverse)

Graffiti on, and defacement of, coinage is known to have occurred, and sometimes carried political messaging, especially in contested political spaces. However, the Σ graffito here respects both the royal obverse portrait and the seated Britannia on the reverse. The symbol is clearly intentional and, repeating on each side, must have carried significant meaning to the person who inscribed it. Sadly its meaning is now lost.

Creating and depositing the hoard (c.1971-1975)

Many coin hoards are discovered buried under ground or below buildings providing a sealed deposit. Once the hoard was deposited in place, it was fixed and nothing further could be added to it. The Castle Street hoard was found in a box at the back of a cupboard upstairs above the shop. While it seemed forgotten about, the box was not a sealed deposit and it is possible that coins may have been added or removed over time.

However, the contents of the hoard does present convincing evidence that it can be viewed as a single unit. The gradual increase in later coins numbers followed by a sharp drop at the point of decimalisation indicates that the hoard is a by-product of that decimalisation process. We know that pre-decimal coins circulated for an extended period of time, evidenced by the increasing wear of the coins in the hoard relative to their dates. The older coins are generally more worn than the more recent issues as would be expected.

It is plausible to suggest that the hoard represents one business or individual’s small change, put aside in the years shortly after the introduction of decimalisation in 1971. Perhaps the box sat by the till, used to collect old money received in payment and put aside so as not to hand it back to another customer as change?

This scenario would also account for the Irish and Manx coinage in the hoard – coins that circulated informally but were not legal tender.

The coins were then put to the back of a cupboard rather than being taken into a bank for exchange, perhaps because of their relatively low value or, quite possibly, because the window of opportunity when the banks would exchange the old currency for new (February-August 1971) had passed, and coins had lost their buying power.

Our thanks to members of the Numismatic Society of Ireland (Northern Branch) whose valuable comments helped tighten up this research.