Private James Henry: A Voice from the Trenches

Museum Services are getting ready for a busy Playful Museums month this February!

29th January 2025The James Henry collection of letters is a remarkable and deeply personal archive that captures one man’s experience of World War I and the life of his family back home in Coleraine. Donated to Coleraine Museum in 2014 by George Leighton, Isobel Trussler (née Leighton), Helen, and their family, this collection offers a rare glimpse into the war through 121 letters and 94 postcards written between October 1915 and October 1918.

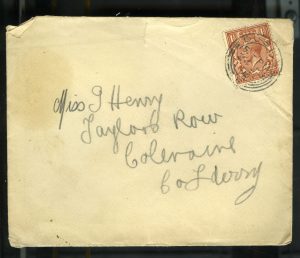

These letters, addressed to James’s father Alexander and sister Georgina, were lovingly preserved by Georgina and passed down through generations. Their excellent condition—despite being over a century old and written in wartime—speaks volumes about the care taken by the family.

Discovering James Henry

Curious to learn more, I began with the 1911 Irish census. The Henry family lived at house 22 in Castleroe: James, his parents Alexander and Anabella, sister Georgina, and brothers Alex and William Irwin. At 18, James worked as a Water Bailiff, while his father was a gardener. Though the letters are addressed to Taylor’s Row, the 1915 Roll of Honour and James’s death notice list the family’s address as Chapel Square—two streets that adjoin.

James was a member of the Ulster Volunteer Force, specifically the 3rd Battalion North Derry Regiment, known as the Bann Valley Battalion. Many Coleraine UVF volunteers, including James, joined the 10th Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, part of the 109th Brigade, 36th Ulster Division.

Life on the Front

James’s first letter from France, dated 7th October 1915, is brief—he simply assures his father of his good health. Over time, the letters reveal more: life near the front lines, encounters with fellow Coleraine men like Sammie Millar, and descriptions of trench warfare.

In November 1915, James writes of his first experience in the trenches:

“We were very lucky, I think there are just a few slightly wounded. I had 2 very narrow escapes myself… it is a devil of a place.”

He frequently asks about life at home, showing deep concern for his family and community. His letters mention local figures like John Biggart and David Platt, both from Taylor’s Row—a street that sent 21 men to war out of 32 houses. Chapel Square sent 8 men from 18 houses. These numbers highlight the profound impact of the war on Coleraine.

The Somme and Beyond

On 1st July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, James writes:

“Just a few lines to let you know that I am well. I am up the line again but I am with another company…”

Later, he reflects:

“To tell you the truth sometimes this week I thought every minute would be my last… we must win at any cost so we must keep in good spirits.”

His letters grow more candid, describing the loss of comrades and the emotional toll of war. In August 1916, he writes:

“My chum was shot dead at my very side…”

Wounds, Recovery, and Return

James was wounded in March 1918 and hospitalized in England and Ireland. He writes from Netley, Castle Hospital in Dublin, and later from Harrowby Camp and Belton Park. Despite his injuries, he remained hopeful and continued to write home.

In October 1918, James returned to France. His final letter, dated 24th October, ends with:

“There should be big changes in a few months now let us hope so anyway…”

Tragically, James Henry was killed in action on 8th November 1918—just three days before the Armistice was signed. He was 26 years old and is buried in Dourlers Communal Cemetery Extension in France. He is commemorated on the Roll of Honour tablet at St Mary’s Church of Ireland in Macosquin.

Legacy of the Letters

James’s letters are more than historical documents—they are a legacy of love, resilience, and community. They offer a deeply human perspective on the Great War and its impact on Coleraine. Through his words, we hear not just the story of one soldier, but the echoes of a town that lived through history. To view the collection, click here.